The continuity of the Christian faith over the centuries serves as a source of encouragement for the contemporary believer. The earliest Christians are linked to us by a real and living communion, a consoling fact which is an essential part of our own celebrations of Eucharist. It is a precious thing when some of the earliest Christian writings survive to instruct and inspire us, and this is particularly true of the works of Justin Martyr (c. 100-c. 165). A Gentile convert to Christianity, Justin is a valuable witness to early Church teaching and practice. He tells us what he had been taught as a convert, and describes the activities and rituals he himself participated in as a Christian believer. Justin wrote as an educated spokesman for the Christian faith, and his articulate writings are made even more poignant by the fact that his witness was eventually sealed by his martyrdom.

In The First Apology, after explaining the Christian faith and answering various criticisms made by pagan intellectuals, Justin towards the very end of the tract describes the Eucharist. He tells how the Christian community gathers together in one place on Sunday morning. First selections from the writings of the prophets and the Gospels are read aloud, followed by a homily given by the president of the assembly. All then rise and pray together, followed by a prayer of thanksgiving offered by the presider over the gifts of bread and wine mixed with water. Those present then receive the consecrated elements. Justin stresses that only those who are baptized, truly penitent and accept the Christian faith can be allowed to participate in these sacred mysteries:

And this food is called among us the Eucharist, of which no one is allowed to partake but the one who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.”

Justin stresses the apostolic origin of this faith and practice by citing New Testament texts. As beautiful and meaningful as this partaking of the Body and Blood of Christ in the assembly is, there is more to the Eucharist than this. Deacons are to bring the Eucharist to those who are sick or otherwise unable to attend. Although absent from the assembly in physical terms, they too will share in its fellowship and communion, the reality of its life-giving power. Finally, an integral part of the Eucharist is the collection and distribution of alms for those in need:

“And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows, and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds, and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.”

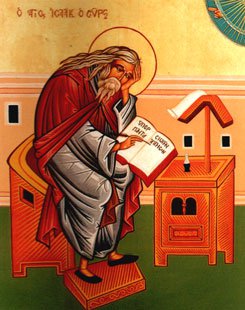

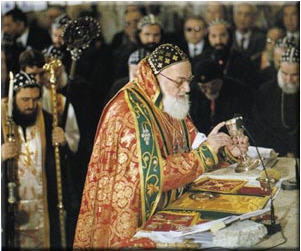

A third century fresco showing the Eucharist

As Justin describes it, the prayer of the assembly, led by the presiding celebrant and sealed by the “Amen” of the congregation, is the glue which holds the Christian community together throughout the week. The Eucharist is the special time when they gather to listen to the scriptures, receive moral exhortation, offer prayers of petition, and receive the Body and Blood of their Savior. What happened during this quiet time, early in the morning on the day of the week on which Christ rose from the dead, gave them the strength to serve those in need, and witness together to the world.

Despite all of our words, the Eucharist remains a Mystery, just as it did in Justin’s day. Our attempts to explain what happens at the eucharistic celebration may be inadequate, but our subsequent actions can demonstrate a loving reality which animates the life of the Church, and show that the Eucharist, and all occasions on which we gather together for prayer, really does make a difference in our lives:

“And we afterwards continually remind each other of these things. And the wealthy among us help the needy; and we always keep together; and for all things wherewith we are supplied, we bless the Maker of all through His Son Jesus Christ, and through the Holy Ghost.”

All quotations from The First Apology of Justin, found in The Ante-Nicene Fathers.Volume I. Republished by Eerdmans, 1989.