What follows is the homily I delivered at All Saints, St Andrews, for the feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Given at All Saints, St Andrews, Assumption 2016.

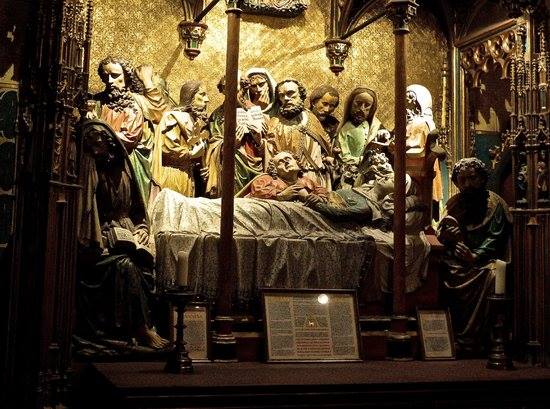

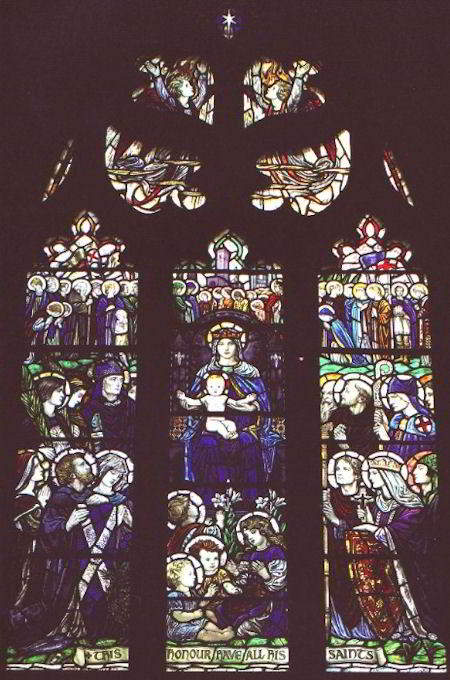

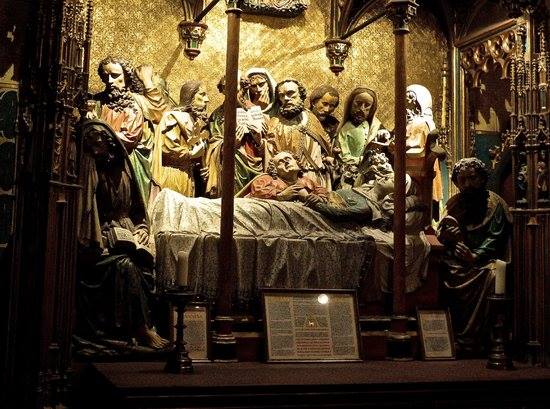

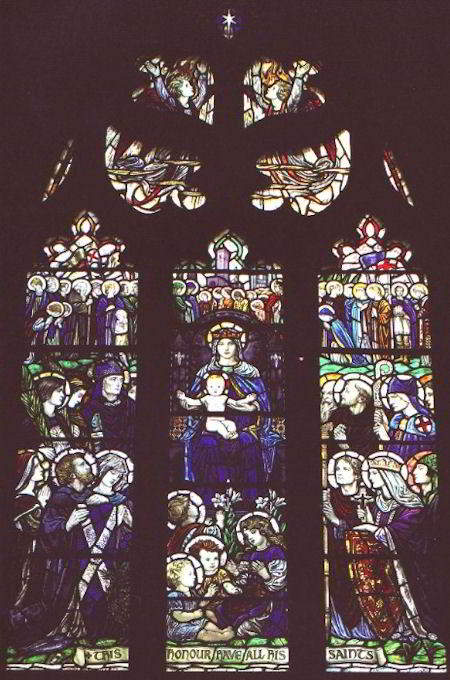

Today we commemorate a great mystery, surrounded in this church by lovely images and sculpture of the Virgin Mary. This is the day of her passing from this life to the next, in the East emphasizing her Dormition or falling asleep, in the West, while this remains a very important aspect of the mystery and how it is portrayed in art, such as in the fifteenth century sculpture in Frankfurt cathedral, the emphasis in recent centuries has been upon her bodily assumption, a precursor, we hope, following in her footsteps, of the resurrection of own body and its eternal glory in heaven united to our soul. So this is a feast not only about the Virgin Mary, but really about our whole destiny as human beings. It is a time for rejoicing in the face of profound mystery, as an ancient antiphon puts it: “Let us all rejoice in the Lord, celebrating the feast day in honour of Blessed Mary the Virgin: in whose Assumption the Angels rejoice, and highly extol the Son of God.”

The Dormition of Our Lady, Frankfurt cathedral, 15th century.

Yes, the Son of God, and also the son of Mary. At the heart of what we celebrate today is in fact a poignant emphasis on the Humanity of Christ, with prayerful reflection on the nature of Christ’s existence from his infancy and early childhood, through his ministry of preaching, and above all in the suffering he endured for humankind during his Passion. This devotional focus manifested itself in manifold ways in the liturgy, art and literature of Christendom. In turn, this devotion to the humanity of Christ also increased attention upon the role of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, in the Christian story, and the implications of Mary’s role in the lives of believers. For after all, in considering the life of Christ as the central drama of all human history, who else was there, from the moment of his conception? who also nurtured and taught him through his childhood? who also was present at his first miracle and throughout his ministry, and who, with a mother’s compassionate grief, also witnessed his torture and crucifixion, standing at the foot of the Cross, and also his death and burial? And then felt the inexpressible joy of experiencing her Son alive again, being present at the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost? Who else, due to the glorious mystery of her Assumption after death, is present body and soul with Jesus in heaven, an active intercessor for humanity while at the same time an intense contemplative of her Son and the Blessed Trinity?

Heinrich Bullinger, a Reformed pastor of Zurich who had a very important influence on the 16th century Reformation in this country, and one whom at first thought we might not find to be supportive of this doctrine, surprisingly expresses his belief that Mary’s “sacrosanctum corpus” (“sacrosanct body”) had been assumed into heaven by angels: as he says in recounting the tradition, “For this reason we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels.”

What does this mean for us? When we look to our earliest traditions, the patristic Christianity of the North, the Anglo Saxon church which wove together so beautifully threads of Germanic, Roman, Celtic and Greek traditions, we get some beautiful clues to who Mary is to us right now. As the Venerable Bede expressed it, commenting on the very gospel we just heard, first of all we wonder at her uniqueness:

“Mary says My soul magnifies the Lord, and this is true of her more than any of the saints, for she rightly exults with more joy in Jesus, that is, in her special Saviour, because she knew that the one whom she had known as the everlasting author of salvation was, in his temporal beginning, to be born of her flesh; in the one and same person he would most truly be both her son and her Lord.”

But as Bede goes on to point out, Mary’s song in the gospel is about all of us, you and me, right here and now:

“Turning from God’s special gifts to herself, to the general decrees of God, Mary speaks of the state of all humankind, as though she were to say: He that is mighty has not only done great things to me; but in every nation he is pleasing to the one who reveres God.”

So let us take hope today on this solemn, festive day, in this season of earthly and spiritual harvest. Let us turn with trust and reverent awe, inspired by these lovely windows, including this one of Mary and all the Scottish saints, to turn into our own heart and mind, to gaze upon Mary who is now where we aspire to be, who points us toward her Son, and let us share in the lovely prayer of an anonymous Anglo Saxon poet, who I think would have appreciated this window of Mary and all saints:

“O splendor of the world,

now show towards us that grace

which the angel, God’s messenger,

brought to you;

reveal to the folk that consolation,

your very own Son.

Then may we all rejoice

When we gaze upon the Child at your breast.

Plead for us now with brave words…

That He may lead us into the kingdom of His father,

Where free from sorrow we may dwell in glory

With the Lord of the heavenly hosts.”

The Blessed Virgin and the Saints of Scotland, in All Saints, St Andrews