If beauty is often found in the most unlikely of places, then from the point of view of the “civilized” world in the seventh century, Ireland was one such unlikely place. Yet at a time when political and ecclesiastical institutions in Western Europe were being shaken to their foundations by war and chaos, Ireland’s remote position on the edge of the western ocean, far from the great Christian centers of the Mediterranean, became its great advantage. Irish monastics preserved and expanded upon the heritage of patristic theology in many areas, including the liturgy.

Due to Ireland’s own tragic experience of of war and invasion later, much of this heritage would in great part be lost. We are fortunate however to have intact a work known as the Bangor Antiphonary, produced in the late seventh century at the Irish monastery of Bangor under the direction of Abbot Cronan. This precious document is the only surviving example of the monastic office for the early Celtic churches and contains many insights on the centrality of the liturgy and the Eucharist in the lives of the faithful at this period in history.

The antiphonary contains seven short scriptural quotations, or “antiphons”, intended for people to recite as they approach communion. They are drawn primarily from the Psalms, both literally or in paraphrase, but also, as the following example shows, from the gospels (John 6:51-52):

This is the living bread which has come down from heaven, alleluia, alleluia.

He who eats of it will live forever, alleluia.

Some of the antiphons are clearly intended to be chanted before the reception of Communion, others in thanksgiving afterwards. We can perhaps learn much about the joyful attitude of these Irish liturgists from the fact that all but one of the eucharistic antiphons contain the word “alleluia.”

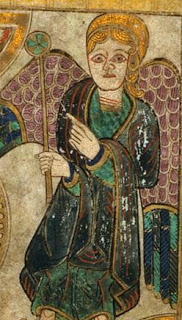

But the shining gem of the Bangor Antiphonary is surely the poem “Sancti, venite,” directed to be sung during the reception of Communion. It certainly dates back well before the seventh century, and legend attaches it to the time of St. Patrick himself. According to the story, the two holy men Patrick and Sechnall had quarreled. When Patrick came to see him, his arrival interrupted Sechnall’s Mass right before the reception of Communion. Sechnall went outside the church to greet Patrick, and the two were reconciled. As they walked together through the cemetery in the churchyard, they heard an angelic choir singing “Sancti, venite, Christi corpus,” and from this point on this angelic hymn was appointed to be sung in Ireland during the reception of Communion.

This story reminds us that even the saints can quarrel, and they too need the eucharist for reconciliation and healing. As their eventful walk through the monastery indicates, the communion of saints extends to the beloved dead and the angels themselves, who are the companions of the living in our spiritual journey.

The ancient Latin hymn itself was translated into English by the great Victorian priest, hymn writer and translator J.M. Neale for The English Hymnal, and from there has made its way into other collections and prayer books.

Fr. Neal’s translation, like the original Latin, is a beautiful expression of patristic eucharistic theology, undoubtedly worthy of the angelic choirs from whom an anonymous Irish monk long ago drew his inspiration:

Holy ones, come, receive the body of Christ, and drink the holy blood by which you are redeemed.

Saved by the body and blood of Christ, fed on them, let us sing praise to God.

By this sacrament of body and blood all are freed from the jaws of Hell.

The Bestower of Salvation, Christ the Son of God, has saved the world by cross and blood.

Sacrificed on behalf of all, the Lord has been himself both priest and victim.

The law wherein sacrifice of victims was bidden is the foreshadowing of the divine mysteries.

The Giver of Light and Saviour of All has granted a glorious grace to His holy ones:

All approach with pure mind and faith to receive an eternal guarantee of salvation.

The Guardian of the saints, their Ruler as well, is the Lord, the Grantor of everlasting life to the faithful.

He gives the bread of heaven tot he hungry, proffers drink to the thirsty from the Living Spring.

Alpha and Omega, Christ the Lord Himself, has come, will come to judge mankind.