Sermon given at All Saints, in St Andrews, July 14, 2019

“But the word is very near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it.” Deuteronomy 30:14.

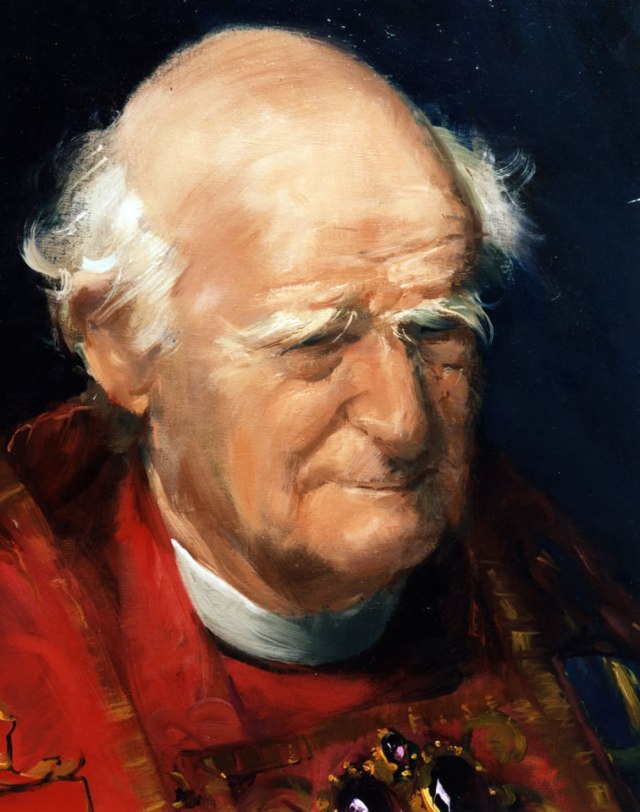

All of us have biblical verses which strike a cord within us and remind us of certain people or moments or events. As I digested the readings this week preparing to preach, this verse from Deuteronomy reminded me of how much over the years I have come to appreciate a humble and unassuming giant of the spiritual life, Br Lawrence of the Resurrection.

Br Lawrence was a seventeenth century Carmelite lay brother in Paris. After years as a soldier, he entered the monastery and spent most of his life doing kitchen chores and repairing sandals for his fellow religious, and gradually became known as a spiritual guide. His letters and sayings were published after his death, and quickly, under the title Practice of the Presence of God, became an instant classic, translated into many languages, including English. There is much wisdom in his simplicity and approach, all focused on calmly throughout the day, in whatever work or occupation one finds oneself, habitually calling gently to mind the presence of God, whom, he came to realize, is never far away, indeed is always at hand and within reach. As Lawrence puts it,

“He does not ask much of us, merely a thought of Him from time to time, a little act of adoration, sometimes to ask for His grace, sometimes to offer Him your sufferings, at other times to thank Him for the graces, past and present, He has bestowed on you, in the midst of your troubles to take solace in Him as often as you can. Lift up your heart to Him during your meals and in company; the least little remembrance will always be the most pleasing to Him. One need not cry out very loudly; He is nearer to us than we think.”

The seventeenth century was a great time of spiritual writers, and many of them devised rather complex forms of meditation. Lawrence tells us that after reading many books about these methods and many headaches in trying to follow them, he came up with a much simpler approach. Lawrence had been a soldier before becoming a Carmelite friar, and that is reflected in the following description of his method:

“A little lifting up of the heart suffices; a little remembrance of God, an interior act of adoration, even though made on the march and with sword in hand, are prayers which, short though they may be, are nevertheless very pleasing to God, and far from making a soldier lose his courage on the most dangerous occasions, bolster it. Let him then think of God as much as possible so that he will gradually become accustomed to this little but holy exercise; no one will notice it and nothing is easier than to repeat often during the day these little acts of interior adoration.”

It is not surprising that this little book about the little way of being Christian has become a classic in the ecumenical sense, and has helped countless Christians of all stripes in their spiritual journey. His deep sense of finding God and abiding in His Presence among the pots and pans, the sewing of sandals, and in every task and every human encounter, can resonate with everyone. This approach, what we might call the Little Way, of joining love and awareness of God with love of neighbor in the small everyday tasks, the stuff of daily existence, is at the heart of Christian life, and is central to the Gospel reading of the Good Samaritan today.

The life of Mother Teresa of Calcutta witnessed an overwhelming response of the Church and much of the world to her simple but profound way of love: doing the humblest things for the humblest people, driven by her desire to love the children of a God who loved us first. Her constant acts of kindness and inclusivity in her idea of neighbor, each perhaps little in itself, amounted to great things that made the world take notice. Likewise, but in a different context, with St. Therese of Lisieux (1873-97), “the Little Flower”. At the heart of her spirituality was the Little Way, of offering not only great suffering up to God, but also the everyday and seemingly trivial difficulties which arise in our daily lives and relationships with others. Such an attitude goes to the very heart of Christ’s relationships with almost everyone he encounters in the Gospels. Likewise, the parables are full of ordinary people, events and things, and opportunities to show love of God and neighbor.

Just a few days ago the Church celebrated the life of one of the most important figures in the whole spiritual tradition, the sixth century monastic teacher St Benedict about whom Gregory the Great wrote a life. As in all medieval hagiographical literature, miracles performed by God through the intercession of the saint form an important part of the story. In Gregory’s Life of St. Benedict, the very first miracle Benedict performs, while still a young man, is to quietly repair a tray which his nurse accidentally broke. As Pope Gregory describes the action:

The poor woman burst into tears; she had just borrowed this tray and now it was ruined. Benedict, who had always been a devout and thoughtful boy, felt sorry for his nurse when he saw her weeping. Quietly picking up both the pieces, he knelt down by himself and prayed earnestly to God, even to the point of tears. No sooner had he finished his prayer than he noticed that the two pieces were joined together again, without even a mark to show where the tray had been broken. Hurrying back at once, he cheerfully reassured his nurse and handed her the tray in perfect condition.1

Benedict would go on to prophesy before kings, found abbeys, heal the sick and even raise the dead, but I am not sure if any of those great works of the Spirit are more beautiful than this prayerful and heartfelt desire to reach out and help a fellow human being in emotional distress. His life and his Holy Rule are full of concern for the little things, such as caring for the sick and extending hospitality to all. Many examples could be given, but his description of the duties of the Cellarer in the monastery is typical, describing him in many of the ways that would fit well the Good Samaritan:

He must show every care and concern for the sick, children, guests and the poor, knowing for certain that he will be held accountable for all of them on the day of judgment. He will regard all utensils and goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar, aware that nothing is to be neglected. He should not be prone to greed, nor be wasteful and extravagant with the goods of the monastery, but should do everything with moderation and according to the abbot’s orders. Above all, let him be humble. If goods are not available to meet a request, he will offer a kind word in reply, for it is written: ‘A kind word is better than the best gift ‘ (Sirach 18:17).

The Rule also says that all guests must be received as if one is receiving Christ, and hospitality is a central part of the Little Way just as it is in monastic life.

Likewise this week our Scottish church remembered another lesser known monk St Drostan, who is particularly venerated in Aberdeenshire. We know little about him, except that most likely he was a disciple and fellow missionary of the great St Columba, and that holy well dedicated to him serves as the water source for Aberlour distillery. But what we really know is that he prayed, recited the Psalms and drew sustenance from the liturgy, and preached and trained others to do so. He baptized and lived in community, being solicitous for the poor, and one miracle for which he is remembered is the simple but kind act of restoring the sight of a priest who had gone blind.

What gave these figures the strength to do these things, to persevere in their spiritual paths? There is a threefold way that prepares us for this, that characterizes this monastic spirituality. One cultivates an attentiveness to God and the needs of our neighbor by first of all living a life based upon praying together in common, through the liturgy, offering our prayers to God as a community as we do this morning, and do week after week, year after year. Secondly, by the prayerful reading of scripture, known as lectio divina, or sacred reading, we ponder over and over the meaning of God’s Word for us. And, thirdly, we do not just think about God and offer up pious thoughts, but we put our faith into action, as the Benedictine motto puts it, ora et labora, prayer and work. Like the cellarer mentioned in the Rule, our work, whatever it is, should be permeated by kindness, outreach to others, an offering lifted up to God, to use another Benedictine motto that is in itself a prayer, “that in all things Christ may be glorified.”

This not just something for monks, and indeed it has long been noted that our Anglican way of worship, though the Book of Common Prayer lived out in parish communities, has deep roots in this Benedictine and wider tradition.

The Anglican monk and spiritual theologian, Bede Thomas Mudge, notes that The Benedictine spirit is certainly at the root of the Anglican way of prayer, in a very special and pronounced manner:

The example and influence of the Benedictine monastery, with its rhythm of divine office and Eucharist, the tradition of learning and ‘lectio divina’, and the family relationship among Abbot and community were determinative for much of Anglican life, and for the pattern of Anglican devotion. This devotional pattern persevered through the spiritual and theological upheavals of the Reformation. The Book of Common Prayer . . . the primary spiritual source-book for Anglicans . . . continued the basic monastic pattern of the Eucharist and the divine office as the principal public forms of worship, and Anglicanism has been unique in this respect.

While this spirituality and discipline, with deep roots in monastic and Anglican tradition, can hopefully prepare us to be attentive to God and neighbor, we must avoid complacency. As the parable of the Good Samaritan shows, merely being an expert on the letter of the Law was not enough to truly discern who your neighbor is, nor does the painstaking performance of ritual automatically prepare us to understand what God wants from us in our everyday encounters with those around us.

The Lawyer answered Jesus correctly on love of God and neighbor as being the heart of the Law, and Jesus tells him to do this, and he shall live. And when in response to the further question of the lawyer, about who is his neighbor, Jesus relates this parable we heard today, and when the lawyer replied that he was a true neighbor to the wounded man who had showed mercy to him, the Lord responds again with a command, “Go, and do in like manner.” That is to say, remember that it is with such prompt mercy you must love and sustain your neighbor who is in need. And by this Christ most clearly revealed to us, that it is love alone, and not love made known by word only, but that which is proved and manifested also by deeds, which brings us to eternal life.

St Benedict and St Drostan and a host of others teach us in their words and deeds that in the guest we receive, in the ones we comfort and support in whatever type of need they are in, that we also do this for Christ. In such acts we perfectly manifest, and make real, love of God and neighbor. We should not excuse ourselves, saying that these matters are too great for us. The Scriptures and the whole tradition of the Little Way, which is in fact a sacred and golden way, tells us that if we cannot do greater things, then let us all help in the lesser things. Help others to live, whether physically or emotionally or spiritually in need. Give food, clothing, medicines, apply remedies to the afflicted, bind up their wounds no matter what type they are, ask about their misfortunes, speak with them of patience and forebearance, draw close to them. It is hard, but we must have confidence that God will supply us with the strength to see Christ in our neighbor. We must let compassion overcome our timidity. We must let the love of our fellow human beings in need overcome the promptings of fear that hold us back. We must not despise our brothers and sisters in need, we must not pass them by.

If I might end with the words of the great patristic writer Gregory of Nazianzus, commenting upon this very Gospel and its implications for all of us, for God, in our hearts and in our neighbor, is indeed closer to us than we might think:

“O servants of Christ, who are my brethren and my fellow heirs, let us, while there is yet time, visit Christ in his sickness, let us care for Christ in His sickness, let us give to Christ to eat, let us clothe Christ in his nakedness. Let us do honour to Christ, and not only at table, as some did, not only with precious ointments, as Mary did, not only in his tomb, as Joseph of Arimathea did, not only doing him honour with gold, frankincense and myrrh, as the Magi did. But let us honour Him because the Lord of all desires from us mercy and not sacrifice, and goodness of heart above thousands of fat lambs. Let us give him this honour in his poor, in those who lie on the ground here before us this very day, (stricken by wounds both seen and unseen), so that when we leave this world they may receive us into eternal tabernacles, in Jesus Christ our Lord, to Whom be there Glory for all ages, Amen.”

Rembrandt. The Good Samaritan.