Sermon on Transfiguration, given at All Saints Church St Andrews, 6 August 2017

“This is my beloved Son, hear him.”

Sometimes in reading Scripture, some of the most important conversations happen off stage, so to speak, and I for one wonder what they are saying. You may have your own examples of this, and for me, two stand out. For instance, how about the Disciples speaking with Jesus on the Road to Emmaus after the Resurrection? What exactly did Jesus say, and how did he say it, to make their hearts burn like fire within their breasts? In today’s great mystery, what were Moses and Elijah saying when they stood there in the presence of the Transfigured Christ? Like the 3 apostles present, were they wondering who this Jesus was, who was so clearly resplendent in Glory?

For he was beautiful, and glorious, and awful to behold, shining with the light of divinity, and, significantly, was this way even before he had died and risen from the dead. And Elijah and Moses, the text tells us, also were beautiful in his reflected splendour. We must not be afraid of beauty; we must never feel guilty about gazing upon and resting in admirable awe in the presence of beauty in God’s good creation. For Jesus was transfigured, revealed to us as he truly was at all times, even before his resurrection, for those capable of seeing, whom he briefly allows to see Him thus, and also showing us a glimpse of our own destiny:

As Saint Thomas Aquinas put it,

“At his Transfiguration Christ showed his disciples the splendor of his beauty, to which he will shape and color those who are his: ‘He will reform our lowness configured to the body of his glory.'”

Now there are many possible things this mystery teaches us.

First and foremost that Jesus Christ is both God and man, and is the beloved of the Father. Secondly, that there is a deep harmony which exists between the Old and the New Testaments regarding Christ, made clear to us by the visible presence of Moses and Elijah.

But in this emphasis on glory and fulfillment of ancient promise, there is even a deeper mystery. Even before the Transfiguration became a feast day in the western church, this Gospel was read on the first Sunday of Lent. It follows in the narrative when Christ has set his face towards Jerusalem, and all that would entail, both for him but also for the disciples, including and perhaps especially Peter who had just ecstatically confessed his belief in Him, and who had also wanted to dissuade Jesus from going to Jerusalem. We must remember this event is a stage to the Cross, as the ancient liturgical cycle and the words themselves teach us; and the Cross, just as it must not be separated from the resurrection which will follow it, must also not be separated from the Transfiguration which preceded it.

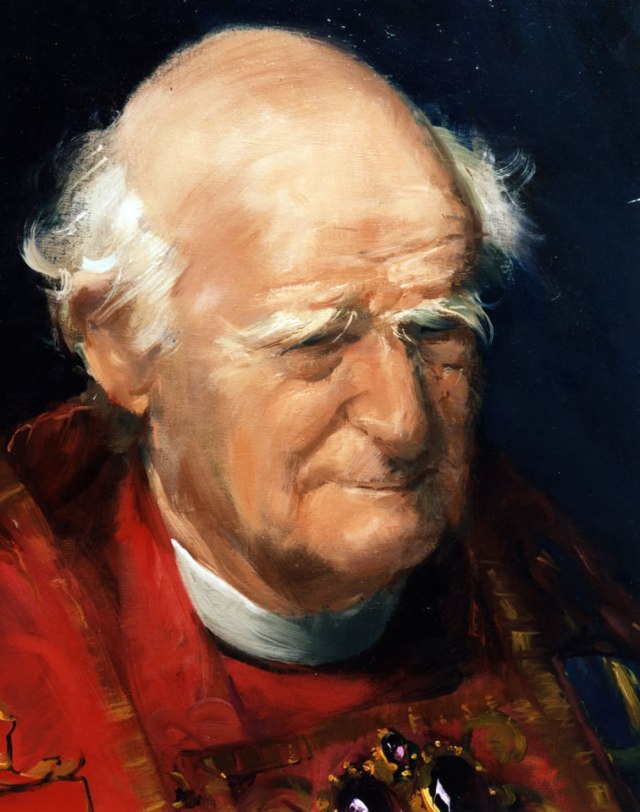

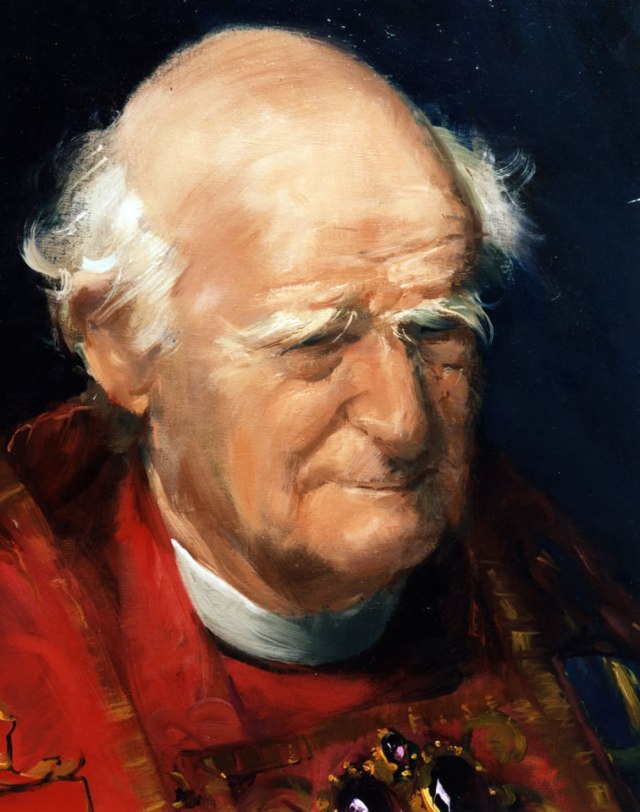

As the text indicates, Moses and Elijah were also in splendor as they discussed this very thing, this approaching Passion, with Jesus. And it would be nice to stay on that mountain, basking in the glory of the Lord, nice for Peter, and nice for us, but as real as this light and glory of Mt Tabor was and is, it is not separated, for either Jesus or for us, by the reality of Calvary. As Archbishop Michael Ramsey put it, in the midst of a world too easily dominated by the shadow of Calvary, we must ever look for signs of God’s ability and power to transform even the ugliest of the realities of sin and despair into moments for a more powerful light to break though and transform all around us, right here and now:

“Confronted with a universe more terrible than ever in the blindness and the destructiveness of its potentialities, men and women must be led to Christian faith, not as a panacea of progress or as an otherworldly solution unrelated to history, but as a gospel of Transfiguration. Such a gospel transcends the world and yet speaks directly to the immediate here-and-now. He who is transfigured is the Son of Man; and as he discloses on the holy mountain another world, he reveals that no part of created things, and no moment of created time lies outside the power of the Spirit, who is Lord, to change it from glory to glory. “

As Archbishop Ramsey continues to tell us in his famous book on the Transfiguration, the Eastern Church has always been much more comfortable with this language, of keeping Transfiguration always before us, the transforming presence of the light of Mt Tabor, present already in our lives here and now, perceptible for those with eyes to see, than in the West.

But if we look to the earliest days of Christianity in Scotland, the life of St Columba, we find this language wonderfully present in several stories about Columba handed down by his disciples. One story tells us that while Columba presided at the Eucharist, a visiting saint noticed a shining ball of light around Columba’s head, and a column of light surrounding him until the Eucharist ended. Another story relates directly to the Transfiguration, as it focuses on opening up the meaning of Scripture. A fellow monk, who admitted he was terrified afterwards until Columba consoled him, witnessed the following:

“On another occasion when St Columba was living in Hinba, the grace of the Holy Spirit was poured upon him in incomparable abundance and miraculously remained over him for three days. During that time he remained day and night locked in his house, which was filled with heavenly light. No one was allowed to go near him, and he neither ate nor drank. But from the house rays of brilliant light could be seen at night, escaping through the chinks of the doors and through the keyholes. He was also heard singing spiritual chants of a kind never heard before. And, as he afterwards admitted to a few people, he was able to see openly revealed many secrets that had been hidden since the world began, while all that was most dark and difficult in the sacred scriptures lay open, plain, and clearer than light in the sight of his most pure heart.”

We may not be granted such moments very often, and, like St Columba’s disciple, perhaps we would not always know what to do with them if we were! But we do experience humbler visions all the time when we see people around us, through acts of love and charity and forgiveness manifest purity of heart, and truly are transfigured into angels of light. When one has the grace to sense a strong experience of God, it is as though seeing something similar to what the disciples experienced during the Transfiguration: For a moment they experienced ahead of time something that will constitute the happiness of paradise. In general, it is brief experiences that God grants on occasions, especially in anticipation of harsh trials. However, no one lives “on Tabor” while on earth, and we must acknowledge this. But as Pope Benedict XVI recently wrote in a talk given on this very feast, we do have a sure way to nourish the light within us, and this is by learning how to listen to the word of God:

“Human existence is a journey of faith and, as such, goes forward more in darkness than in full light, with moments of obscurity and even profound darkness. While we are here, our relationship with God develops more with listening than with seeing; and even contemplation takes place, so to speak, with closed eyes, thanks to the interior light lit in us by the word of God.”

When I think back to my first memories of this story, I remember that it made me want to know much more about who Moses and Elijah were, and how what they were saying and doing pointed to Jesus. This Transfiguration story points us to the Scriptures, encourages us to ponder them again, Old Testament along with the actual words of Jesus. I have come to feel that this feast among many other things that it represents, is also a celebration of the Word of God, and the act of pondering it, praying over it, and listening to what it tells us to do and how to be. As we are but a few days from Lammas, the celebration of the first loaf made from the harvest, I would like to share a lovely quotation from the fourth century theologian Ephraim the Syrian, which employs this harvest imagery, significantly as the opening of our oldest preserved full sermon on the Transfiguration:

“The harvest comes joyfully from the fields, and a yield that is rich and pleasant from the vine; and from the Scriptures teaching that is life giving and salutary. The fields have but one season of harvest; but from the Scripture there gushes forth a stream of saving doctrine. The field when reaped lies idle, and at rest, and the branches when the vine is stripped lie withered and dead. The Scriptures are garnered each day, yet the years of its interpreters never come to an end; and the clusters of its vines, which in it are close to those of hope, though also gathered each day, are likewise without end. Let us therefore come to this field, and take our delight of its life giving furrows; and let us reap there the wheat of life, that is the words of Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

If we desire enlightenment, ponder the scriptures; ponder the prophets, ponder the law, ponder the proverbs and psalms, all in light of the teaching of Jesus Christ; do all in our power to be open to this light and illumination, and listen in serious delight to Jesus over and over again; ponder who he is, the Transfigured One who yet humbled himself to die on a cross, and who then rose again, and let his words sink into the very depths of our being, allowing us to be transfigured in his image and likeness; as an old American hymn that I learned in my childhood put it, describing Jesus: “In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea, with a glory in his bosom which transfigures you and me”. The Father’s testimony is meant to raise us up and strengthen our own infirmity of Spirit, and help us remember the implications of what it truly means to be brothers and sisters of Jesus, made in the image and likeness of God.

As Pope Leo the Great concludes his sermon on this great mystery, the oldest sermon on the Transfiguration we have in the Western church, he dwells upon the command of the Father, “Listen to Him”.

“Without delay therefore hear Him Whom in all things I am well pleased; in preaching Whom I am made known; in whose lowliness I am glorified; for He is the Truth and the Life, He is my power, My wisdom. “hear ye Him” whom the mysteries of the Law foretold; whom the mouths of the prophets proclaimed. “hear ye him” Whose Blood has redeemed the world; Who has chained the demon, and taken from him what he held; Who has blotted out the deeds of sin, the covenant of evildoing. “hear ye him” Who opens the way to heaven, and though the humiliation of the Cross prepared for you a way to ascend to his kingdom. “ Amen.