Here follows a sermon I gave at All Saints Church, St Andrews, February 2, 2020.

“Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace according to thy word.

For mine eyes have seen thy salvation,

Which thou hast prepared before the face of all people;

To be a light to lighten the Gentiles and to be the glory of thy people Israel.”

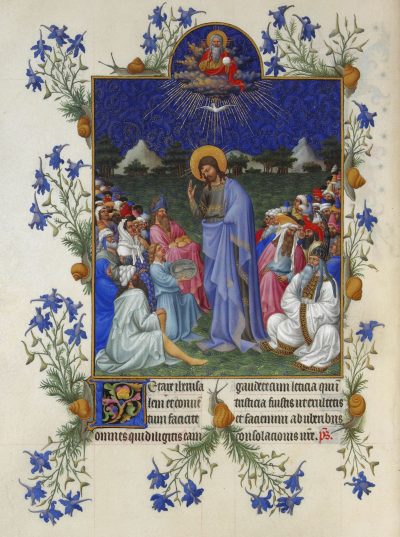

Today, Candlemas, is the traditional culmination of the whole season of Christmas. The Infancy Narratives (the first two chapters of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke) are marked by powerful moments of divine annunciations and epiphanies, as well as by human and angelic response in song. These accounts of the birth and childhood of Jesus have served as profound inspiration for Christian theology and art throughout history, and the truths they embody are central to the Christian imagination. We have journeyed through the birth of John the Baptist, as well as of the events surrounding and following the nativity and epiphany of Jesus. Far from seeing the infancy narratives as a charming prelude to the main events of the Gospel, made up after the facts, we can see in them an indispensable summation of the main themes of the Christian faith, and, more specifically, the fulfillment of the promises of the Old Testament in the coming of Jesus Christ, and our own place in all of this.

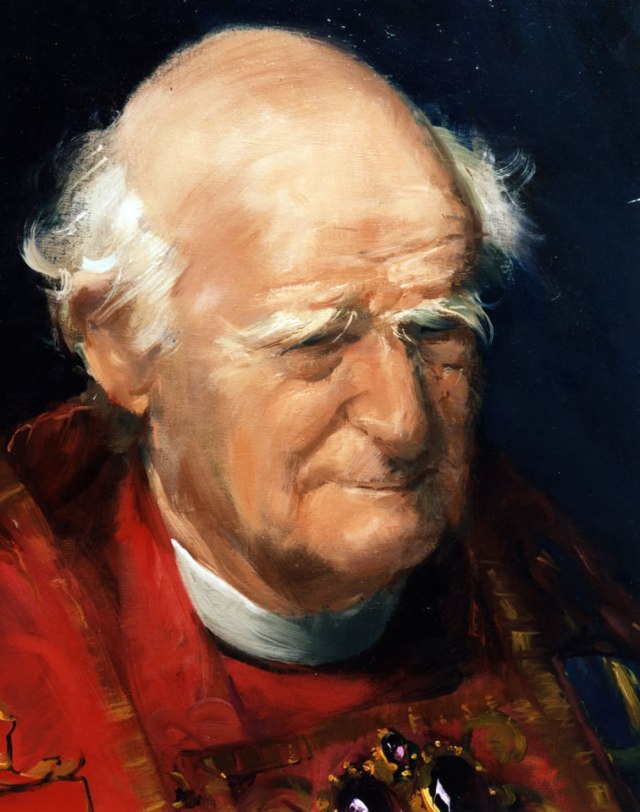

The culmination of the Infancy Narratives is the very feast we celebrate today, sometimes known by its earlier designation as the Purification of the Virgin Mary, sometimes the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, and Candlemas because of the blessing of candles and procession which we undertook today. Over the centuries, this is seen as an episode where both Christ and his Mother, through his presentation and her ritual purification after giving birth, submit themselves to the Jewish law. This, tradition tells us, is a profound act of humility, for such purification is needed, in fact, by neither of them. The infant Christ is presented to the elderly Simeon who, embodying Old Testament wisdom, is enabled to experience the promised, but long-awaited consolation of Israel. His ecstatic song, known as Nunc dimittis by its opening word in Latin, is sung every night by the Church in either Evensong or Compline. The medieval theologian Bonaventure feels this is quite fitting, as it encapsulates the whole gospel story and its central theological meaning:

“Thus in this canticle Christ is praised as peace, salvation, light and glory. He is peace, because he is the mediator. He is salvation, because he is the redeemer. He is light, because he is the teacher. He is glory, because he is the rewarder. And in these four consist the perfect commendation and magnification of Christ, indeed the most brief capsulation of the entire evangelical story: incarnation in peace; preaching in light; redemption in salvation; resurrection in glory.”

For Bonaventure, Simeon can only be explained in light of Old Testament scriptures because he is the representative of the just man, responding for all the just who had come before him and had longed to see this day. Besides Simeon being the fulfillment of Scriptural descriptions of the just man, the embodiment of Wisdom literature, Bonaventure tells us how the Holy Spirit continued to speak to Simeon through the Scripture, making more annunciations: especially on the theme of looking for the consolation of Israel: “Thus the Holy Spirit in a most powerful way said to him what is read in Habbakuk 2:3 :if he tarries a little, look for him, for he will surely come and will not delay.” Bonaventure argues that the Spirit was present with Simeon through grace and love, Simeon also received, in response to his long years of prayer, a special response of Revelation, that is from the Holy Spirit. [As Bonaventure says,] “Finally, Simeon was told by the Spirit of truth, and prompted to comprehension infused with Joy, that he himself would meet the Lord with the suddenness promised in Malachi 3:1:Behold I send my angel and he shall prepare the way before my face. And presently the Lord, whom you seek, and the angel of the testament, whom you desire, shall come to his temple. Behold he is coming, proclaims the Lord of hosts.

Then Bonaventure moves to the romantic imagery of the Song of Songs, and urges us to imitate the behavior of the elderly Simeon who let down his inhibitions and embraced the infant Jesus: “Let love overcome your bashfulness; let affection dispel your fear. Receive the infant in your arms and say with the bride I took hold of him and would not let go (Song of Songs 3:4).”

Bonaventure then turns to another key figure in this episode, the prophetess and aged widow Anna. As his discussion of her demonstrates, there is even more theological richness to be found in this episode. Bonaventure tells us he will describe why Anna herself is a suitable witness to these great events, but first he makes an important digression to assert that witnesses were needed from every stage of life and both genders, as Christ was coming to restore everything and everyone:

“After the testimony of an elderly man there now follows the testimony from a woman. For it is fitting that there be testimony to the advent of Christ from every sort of person, so that those who do not believe the Gospel might be without excuse. Whence there was angelic and human testimony to Christ, and also of the simple and of the perfect of both sexes to show that both sexes looked for redemption just as both had fallen. Therefore to show that there was no crack in the firm foundation of the testimony, there was sevenfold testimony to the birth of Christ.”

This sevenfold testimony as shown in the Christmas story, of how all creation must witness to the birth of the redeemer: 1) heavenly testimony from the star 2) source above heaven, the angels ; 3) from under heaven, simple folk like shepherds ; 4) wise men like the magi ; 5) elderly men, like Simeon ; 6) elderly women like Anna; 7) even infants who gave their lives, that is the Holy Innocents in Bethlehem;. “And every nature, every sex, every age produced testimony to the birth of Christ, because he had to restore all things.”) Bonaventure sums this point up dramatically by citing Luke 19:40 about how all things, even the stones and material world, will cry out in response to God’s appearance among us, even if some keep silence. As Simeon is the fulfillment of all the just men of the Old Testament, so Mary and the Prophetess Anna could be seen as functioning in the same way for all of the Old Testament women who responded to God, whether in their prophecies, laments, songs of praise and periods of thoughtful and profound silence.

But there is another part of Simeon’s words which give us pause, as with one eye we look back and marvel with the events of Christmas and Epiphany. For Simeon also suddenly gazes forward in time and speaks to Mary his prophecy about Christ being the rise and fall of many, and that a sword will pierce her heart. This episode plays an almost unique role in the later medieval devotional tradition, forming as it does, along with the Finding of Christ in the Temple at the age of Twelve, one of the Joyful Mysteries of the Rosary, but also one of the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin Mary. This complexity of the episode reflects that while the parents of Jesus are marveling at Simeon’s words, the elderly man then prophetically indicates doleful things in Mary’s future; as one commentator puts it, “In a stage whisper Luke announces the Cross.” In this way, there is a poignant combination of Joy and Sorrow which attends this mystery and gives it more depth and matter for reflection, a fitting hinge in the calendar between Christmastide and Lent.

![]()

And in fact Mystery is the word, for so much is hidden here, like in all the Infancy Narratives, in seemingly simple dress. For when we think of God, the awesome and infinite God, all powerful and all knowing, at times he can seem so totally other and far beyond us. As the fifteenth century theologian Nicholas of Cusa put it speaking to God,

“Moreover, if anyone expresses any likeness and maintains that You are to be conceived in accordance with it, I know as well that this likeness is not a likeness of You. Similarly, if anyone recounts his understanding of You, intending to offer a means for Your being understood, he is still far away from You. For You are separated by a very high wall from all these [modes of apprehending]. For [this] wall separates from You whatever can be spoken of or thought of, because You are free from all the things that can be captured by any concept. Hence, even when I am very highly elevated, I see that You are Infinity. Consequently, You are not approachable, not comprehensible, not nameable, not manifold, and not visible.”

Yet, as Cusanus continues, and as we celebrate today, in Jesus Christ somehow God has nevertheless made himself approachable and accessible. He is our way of approaching God. In becoming one of us, God is eminently approachable. We are called today to do something as simple as to “walk forth to meet the mother and child”. As we did so in procession earlier, let us do so shortly in another procession. To the altar to receive Him in communion. Let us walk forth to meet him, conscious of the Joy of Christmas, conscious also of what he did for us on the Cross, and what he does now.

For this “now” that Simeon sings about, his moment of meeting God, is also a Now for us. As the priest and poet John Donne wrote centuries ago reflecting on this song of Simeon in its relation to us about to receive Christ in the Eucharist:.

“For mine eyes have seen thy salvation; Now, now the time is fulfilled! And all the way, in every step that we make, in his light (in Simeon’s light) we shall see light; we shall consider that that preparation and disposition, and acquiescence which Simeon had in his Epiphany, in his visible seeing of Christ then, is offered to us in this Epiphany, in this manifestation and application of Christ in the Sacrament.”

Thus, to carry a lighted candle as we did today is a profession of faith. By that little ceremony you say that you have Christ, that you believe in Him, hope in Him, and love Him, and that you are willing to be consumed, burnt up for Him.

The world today, all of us, need Christ, we are hungry for Him without knowing it; we are at times in the dark. We can help bring light, bring it to each other. The lighted candle tells us so. We need but be more fervent in our own Christian and religious life, more faithful to our daily duties, more patient in our daily crosses. This is to preach Christ, to let Christ’s light shine to all people. A quiet, humble, holy life is the best of sermons.The blessed candle, in its simplicity and power, reminds us all of this.

To end with the words of St Sophronius of Jerusalem, preached to his people some 14 centuries ago,

Our lighted candles are a sign of the divine splendor of the one who comes to expel the dark shadows of evil and to make the whole universe radiant with the brilliance of his eternal light. Our candles also show how bright our souls should be when we go to meet Christ…..

The true light has come, the light that enlightens every man who is born into this world. Let all of us, my brethren, be enlightened and made radiant by this light. Let all of us share in its splendor, and be so filled with it that no one remains in the darkness. Let us be shining ourselves as we go together to meet and to receive with the aged Simeon the light whose brilliance is eternal.

Amen.