A recent book chapter of mine on St Bonaventure , Old Testament typology and the Liturgy can be found here: CLICK HERE

A recent book chapter of mine on St Bonaventure , Old Testament typology and the Liturgy can be found here: CLICK HERE

Sermon given at All Saints, in St Andrews, July 14, 2019

“But the word is very near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it.” Deuteronomy 30:14.

All of us have biblical verses which strike a cord within us and remind us of certain people or moments or events. As I digested the readings this week preparing to preach, this verse from Deuteronomy reminded me of how much over the years I have come to appreciate a humble and unassuming giant of the spiritual life, Br Lawrence of the Resurrection.

Br Lawrence was a seventeenth century Carmelite lay brother in Paris. After years as a soldier, he entered the monastery and spent most of his life doing kitchen chores and repairing sandals for his fellow religious, and gradually became known as a spiritual guide. His letters and sayings were published after his death, and quickly, under the title Practice of the Presence of God, became an instant classic, translated into many languages, including English. There is much wisdom in his simplicity and approach, all focused on calmly throughout the day, in whatever work or occupation one finds oneself, habitually calling gently to mind the presence of God, whom, he came to realize, is never far away, indeed is always at hand and within reach. As Lawrence puts it,

“He does not ask much of us, merely a thought of Him from time to time, a little act of adoration, sometimes to ask for His grace, sometimes to offer Him your sufferings, at other times to thank Him for the graces, past and present, He has bestowed on you, in the midst of your troubles to take solace in Him as often as you can. Lift up your heart to Him during your meals and in company; the least little remembrance will always be the most pleasing to Him. One need not cry out very loudly; He is nearer to us than we think.”

The seventeenth century was a great time of spiritual writers, and many of them devised rather complex forms of meditation. Lawrence tells us that after reading many books about these methods and many headaches in trying to follow them, he came up with a much simpler approach. Lawrence had been a soldier before becoming a Carmelite friar, and that is reflected in the following description of his method:

“A little lifting up of the heart suffices; a little remembrance of God, an interior act of adoration, even though made on the march and with sword in hand, are prayers which, short though they may be, are nevertheless very pleasing to God, and far from making a soldier lose his courage on the most dangerous occasions, bolster it. Let him then think of God as much as possible so that he will gradually become accustomed to this little but holy exercise; no one will notice it and nothing is easier than to repeat often during the day these little acts of interior adoration.”

It is not surprising that this little book about the little way of being Christian has become a classic in the ecumenical sense, and has helped countless Christians of all stripes in their spiritual journey. His deep sense of finding God and abiding in His Presence among the pots and pans, the sewing of sandals, and in every task and every human encounter, can resonate with everyone. This approach, what we might call the Little Way, of joining love and awareness of God with love of neighbor in the small everyday tasks, the stuff of daily existence, is at the heart of Christian life, and is central to the Gospel reading of the Good Samaritan today.

The life of Mother Teresa of Calcutta witnessed an overwhelming response of the Church and much of the world to her simple but profound way of love: doing the humblest things for the humblest people, driven by her desire to love the children of a God who loved us first. Her constant acts of kindness and inclusivity in her idea of neighbor, each perhaps little in itself, amounted to great things that made the world take notice. Likewise, but in a different context, with St. Therese of Lisieux (1873-97), “the Little Flower”. At the heart of her spirituality was the Little Way, of offering not only great suffering up to God, but also the everyday and seemingly trivial difficulties which arise in our daily lives and relationships with others. Such an attitude goes to the very heart of Christ’s relationships with almost everyone he encounters in the Gospels. Likewise, the parables are full of ordinary people, events and things, and opportunities to show love of God and neighbor.

Just a few days ago the Church celebrated the life of one of the most important figures in the whole spiritual tradition, the sixth century monastic teacher St Benedict about whom Gregory the Great wrote a life. As in all medieval hagiographical literature, miracles performed by God through the intercession of the saint form an important part of the story. In Gregory’s Life of St. Benedict, the very first miracle Benedict performs, while still a young man, is to quietly repair a tray which his nurse accidentally broke. As Pope Gregory describes the action:

The poor woman burst into tears; she had just borrowed this tray and now it was ruined. Benedict, who had always been a devout and thoughtful boy, felt sorry for his nurse when he saw her weeping. Quietly picking up both the pieces, he knelt down by himself and prayed earnestly to God, even to the point of tears. No sooner had he finished his prayer than he noticed that the two pieces were joined together again, without even a mark to show where the tray had been broken. Hurrying back at once, he cheerfully reassured his nurse and handed her the tray in perfect condition.1

Benedict would go on to prophesy before kings, found abbeys, heal the sick and even raise the dead, but I am not sure if any of those great works of the Spirit are more beautiful than this prayerful and heartfelt desire to reach out and help a fellow human being in emotional distress. His life and his Holy Rule are full of concern for the little things, such as caring for the sick and extending hospitality to all. Many examples could be given, but his description of the duties of the Cellarer in the monastery is typical, describing him in many of the ways that would fit well the Good Samaritan:

He must show every care and concern for the sick, children, guests and the poor, knowing for certain that he will be held accountable for all of them on the day of judgment. He will regard all utensils and goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar, aware that nothing is to be neglected. He should not be prone to greed, nor be wasteful and extravagant with the goods of the monastery, but should do everything with moderation and according to the abbot’s orders. Above all, let him be humble. If goods are not available to meet a request, he will offer a kind word in reply, for it is written: ‘A kind word is better than the best gift ‘ (Sirach 18:17).

The Rule also says that all guests must be received as if one is receiving Christ, and hospitality is a central part of the Little Way just as it is in monastic life.

Likewise this week our Scottish church remembered another lesser known monk St Drostan, who is particularly venerated in Aberdeenshire. We know little about him, except that most likely he was a disciple and fellow missionary of the great St Columba, and that holy well dedicated to him serves as the water source for Aberlour distillery. But what we really know is that he prayed, recited the Psalms and drew sustenance from the liturgy, and preached and trained others to do so. He baptized and lived in community, being solicitous for the poor, and one miracle for which he is remembered is the simple but kind act of restoring the sight of a priest who had gone blind.

What gave these figures the strength to do these things, to persevere in their spiritual paths? There is a threefold way that prepares us for this, that characterizes this monastic spirituality. One cultivates an attentiveness to God and the needs of our neighbor by first of all living a life based upon praying together in common, through the liturgy, offering our prayers to God as a community as we do this morning, and do week after week, year after year. Secondly, by the prayerful reading of scripture, known as lectio divina, or sacred reading, we ponder over and over the meaning of God’s Word for us. And, thirdly, we do not just think about God and offer up pious thoughts, but we put our faith into action, as the Benedictine motto puts it, ora et labora, prayer and work. Like the cellarer mentioned in the Rule, our work, whatever it is, should be permeated by kindness, outreach to others, an offering lifted up to God, to use another Benedictine motto that is in itself a prayer, “that in all things Christ may be glorified.”

This not just something for monks, and indeed it has long been noted that our Anglican way of worship, though the Book of Common Prayer lived out in parish communities, has deep roots in this Benedictine and wider tradition.

The Anglican monk and spiritual theologian, Bede Thomas Mudge, notes that The Benedictine spirit is certainly at the root of the Anglican way of prayer, in a very special and pronounced manner:

The example and influence of the Benedictine monastery, with its rhythm of divine office and Eucharist, the tradition of learning and ‘lectio divina’, and the family relationship among Abbot and community were determinative for much of Anglican life, and for the pattern of Anglican devotion. This devotional pattern persevered through the spiritual and theological upheavals of the Reformation. The Book of Common Prayer . . . the primary spiritual source-book for Anglicans . . . continued the basic monastic pattern of the Eucharist and the divine office as the principal public forms of worship, and Anglicanism has been unique in this respect.

While this spirituality and discipline, with deep roots in monastic and Anglican tradition, can hopefully prepare us to be attentive to God and neighbor, we must avoid complacency. As the parable of the Good Samaritan shows, merely being an expert on the letter of the Law was not enough to truly discern who your neighbor is, nor does the painstaking performance of ritual automatically prepare us to understand what God wants from us in our everyday encounters with those around us.

The Lawyer answered Jesus correctly on love of God and neighbor as being the heart of the Law, and Jesus tells him to do this, and he shall live. And when in response to the further question of the lawyer, about who is his neighbor, Jesus relates this parable we heard today, and when the lawyer replied that he was a true neighbor to the wounded man who had showed mercy to him, the Lord responds again with a command, “Go, and do in like manner.” That is to say, remember that it is with such prompt mercy you must love and sustain your neighbor who is in need. And by this Christ most clearly revealed to us, that it is love alone, and not love made known by word only, but that which is proved and manifested also by deeds, which brings us to eternal life.

St Benedict and St Drostan and a host of others teach us in their words and deeds that in the guest we receive, in the ones we comfort and support in whatever type of need they are in, that we also do this for Christ. In such acts we perfectly manifest, and make real, love of God and neighbor. We should not excuse ourselves, saying that these matters are too great for us. The Scriptures and the whole tradition of the Little Way, which is in fact a sacred and golden way, tells us that if we cannot do greater things, then let us all help in the lesser things. Help others to live, whether physically or emotionally or spiritually in need. Give food, clothing, medicines, apply remedies to the afflicted, bind up their wounds no matter what type they are, ask about their misfortunes, speak with them of patience and forebearance, draw close to them. It is hard, but we must have confidence that God will supply us with the strength to see Christ in our neighbor. We must let compassion overcome our timidity. We must let the love of our fellow human beings in need overcome the promptings of fear that hold us back. We must not despise our brothers and sisters in need, we must not pass them by.

If I might end with the words of the great patristic writer Gregory of Nazianzus, commenting upon this very Gospel and its implications for all of us, for God, in our hearts and in our neighbor, is indeed closer to us than we might think:

“O servants of Christ, who are my brethren and my fellow heirs, let us, while there is yet time, visit Christ in his sickness, let us care for Christ in His sickness, let us give to Christ to eat, let us clothe Christ in his nakedness. Let us do honour to Christ, and not only at table, as some did, not only with precious ointments, as Mary did, not only in his tomb, as Joseph of Arimathea did, not only doing him honour with gold, frankincense and myrrh, as the Magi did. But let us honour Him because the Lord of all desires from us mercy and not sacrifice, and goodness of heart above thousands of fat lambs. Let us give him this honour in his poor, in those who lie on the ground here before us this very day, (stricken by wounds both seen and unseen), so that when we leave this world they may receive us into eternal tabernacles, in Jesus Christ our Lord, to Whom be there Glory for all ages, Amen.”

Rembrandt. The Good Samaritan.

The profound and often sublime writings of those early Christians whom we refer to as “Church Fathers” were not the products of people whose only concern was theological speculation. Almost all of these writers were, in fact, extremely busy bishops or pastors who were preoccupied with pragmatic problems of the flock entrusted to them. Sometimes, as in the case of Bishop Cyprian of Carthage (d. 258), they were forced to deal with severe tensions arising from persecution of the church by the Roman authorities. Indeed, the account of Cyprian’s own martyrdom, written by his deacon Pontius, is one of the most sobering and moving in all of early Christian literature.

It is a testament to the seriousness of their faith that learned bishops such as Cyprian took the time amidst other pressing concerns to write about doctrine and defend various Catholic positions. On occasion Cyprian wrote short treatises on various pastoral and doctrinal issues. More often he responded to requests from others to clarify or answer various questions which would arise. Many of these precious epistles have survived, and we are fortunate that in “Letter 63” of this collection Cyprian developed his thoughts on the eucharist, giving valuable insights into the teaching of the Latin church in his day.

The immediate occasion of this letter, addressed to a fellow bishop, was concern that some bishops and priests were celebrating the eucharist without using wine. Rather than mixing wine with water in the chalice, as had been the Catholic practice handed down from apostolic times, these pastors were consecrating water alone. Cyprian condemns this practice and uses the opportunity both to assert the authority of scripture and apostolic tradition, and to explain the symbolic significance of the use of wine in the Eucharist.

Cyprian begins with the initial premise that we must always obey the explicit commands of Christ as found in scripture. Christ used bread and wine at the Last Supper, and the apostle Paul strongly enjoined us to obey the Lord explicitly in this matter. No bishop or anyone else has the authority to change what Christ instituted. Cyprian also develops the idea at some length how the fruit of the vine is essential to the Eucharist. In the Old Testament, wine is used to prefigure the suffering of Christ, and it is this very passion of the Lord which comprises the sacrifice we offer at the altar. To those who would argue that since wine can be abused and lead to drunkenness it is inappropriate for the Eucharist, Cyprian contrasts spiritual and carnal inebriation:

“Actually, the Chalice of the Lord so inebriates that it makes sober, that it raises minds to spiritual wisdom, that from this taste of the world each one comes to the knowledge of God and, as the mind is relaxed by the common wine and the soul is relaxed all sadness is cast away, so, when the Blood of the Lord and the life-giving cup have been drunk, the memory of the old man is cast aside and there is induced forgetfulness of former worldly conversation and the sorrowful and sad heart which was formerly pressed down with distressing sins is now relaxed by the joy of the divine mercy.”

Union with Christ is the purpose of the Eucharist, and that certainly is a cause of inexpressible joy. But at the same time, it is Christ’s passion with which we are called to identify in the Eucharist, not only his glory. In a sobering remark, perhaps foretelling his own martyrdom, Bishop Cyprian notes that we will not be willing to shed our own blood for Christ if we are ashamed to admit the reality that we drink his blood in the Eucharist. But if we love Christ and really believe in what he continues to do for us in the Eucharist, nothing can take this gift away from us. Perhaps the most poignant passage in the letter is Cyprian’s commentary on the act of mixing the wine and water in the chalice during the preparation of the gifts.

“For, because Christ, who bore our sins, also bore us all, we see that people are signified in the water, but in the wine the Blood of Christ is shown. But when water is mixed with wine in the Chalice, the people are united to Christ, and the multitude of the believers is bound and joined to Him in whom they believe. This association and mingling of water and wine are so mixed in the Chalice of the Lord that the mixture cannot be mutually separated. Whence nothing can separate the Church, that is, the multitude established faithfully and firmly in the Church, persevering in that which it has believed, from Christ as long as it clings and remains in undivided love.”

All quotations taken from St. Cyprian. “Letters (1-81)”, Translated by Sister Rose Bernard Donna, C.S.J., Washington, D.C. The Catholic University of America Press.

The Cistercians, ever since my frequent visits to their abbey in Conyers, Georgia while an undergraduate at Emory, have had a deep appeal to me. There are so many great spiritual writers found among them in their earliest flourishing in the mid twelfth century, and one of the finest is Blessed Guerric of Igny (+1157), who with Bernard of Clairvaux, William of St Thierry and Aelred of Reivaulx, is considered one of the “four evangelists of Citeaux”.

We do not know much about Guerric’s early life as a teacher and scholar, but we do know that like so many others he fell under the spell of St Bernard and became a Cistercian monk and then abbot at the new foundation of Igny in France. There he attained a saintly reputation as a scholar and spiritual teacher.

Igny abbey today

Igny has gone through many travails in its long history, suffering much in the French Revolution and modern trials. After various closures and persecutions, it once again flourishes as an abbey for Cistercian nuns, who in their daily lives continue to live out this beautiful tradition of prayer and work, ora et labora, that is at the heart of the Benedictine and Cistercian heritage.

Guerric has left to us fewer writings than many of the other Cistercians mentioned above, but his 54 Liturgical Sermons are a precious and in my opinion unequaled reflection on the meaning of the liturgical year and the Christian way of prayer and salvation. In this beautiful setting of Igny, Guerric set forth for his monks the spiritual riches of the liturgy, and the profound meaning of the important seasons and festivals of the Church year.

As we approach the great feast of Christmas, I would like to share with you two brief passages from Guerric. The first concerns an exhortation to the monastic practice of lectio divina, the prayerful reading of Scripture which the monks and nuns make time for everyday. In one sermon Guerric has this to say:

Search the Scripture. For you are not mistaken in thinking that you find life in them, you who seek nothing else in them but Christ, to whom the Scriptures bear witness. Blessed indeed are they who search his testimonies, seek them out with all their heart. Therefore you who walk about in the gardens of the Scriptures do not pass by heedlessly and idly, but searching each and every word like busy bees gathering honey from flowers, reap the Spirit from the words. (Sermon 54).

This is an invitation in this busy season to take time in the days leading up to Christmas and in the subsequent holiday to quietly and prayerfully read the Infancy Narratives in the first two chapters of Matthew and Luke, and the Prologue to the Gospel of John. Let them speak to your heart, and bring new insights to light, to nourish your soul with these familiar stories in new and even unexpected ways.

In one of his sermons for Advent, in a striking manner Guerric urges us to also cultivate silence in a season not always known in our contemporary society for quiet reflection. Indeed, he strikingly draws upon the imagery of Christ patiently waiting in the womb of his Blessed Mother these days before his birth as a model for our own spiritual practice:

“As the Christ-child in the womb advanced toward birth in a long, deep silence, so does the discipline of silence nourish, form and strengthen a person’s spirit, and produce growth which is the safer and more wholesome for being the more hidden.”(Sermon 28)

May this Advent and Christmastide bring us many moments of productive silence, and a fresh appreciation, with the eyes and ears of a spiritual child of God, of the treasures of familiar yet always new Sacred Scripture, and what the Spirit is trying to teach us through them.

The conventional view of western history sees the conversion of Constantine and the end of Roman persecution of Christians in the fourth century as the beginning of a new relationship between church and state which lasted down to the modern era. However, not all Christians lived in the Roman empire, and many in fact lived in modern Iran, Iraq and other regions of Rome’s bitter political rival, the Persian empire. When the Roman state became Christian in the mid-fourth century, the formerly-tolerant Persian government began to persecute the Church in its own realm. In this atmosphere of persecution and uncertainty, a Christian writer known as Aphrahat “the Persian Sage” produced a series of twenty -three homilies on various themes which have survived and are known as “Demonstrations.”

The Fourth Demonstration concerns prayer, and is the earliest Christian treatise on the subject that is not primarily a commentary on the Lord’s Prayer. In this brief but profound work, Aphrahat has much to say about the proper approach to liturgical prayer, as is clear from the opening sentence:

“Purity of heart constitutes prayer more than do all the prayers that are uttered out aloud, and silence united to a mind that is sincere is better than the loud voice of someone crying out.”

Aphrahat of course is not saying that vocal prayer is unimportant or inappropriate, but rather that singing hymns or saying responses in itself does not constitute true liturgical prayer. The words we say must be united to what spiritual writers call “mind and heart” for them to become real prayers. Aphrahat’s comment on the importance of silence is also noteworthy. Lectors, cantors and celebrants must take special care to ensure that moments of reflective silence are prominent in the Eucharist. Incidental chatter and unnecessary explanations and announcements on the one hand, as well as rushing from one part of the Mass to the next, can destroy the moments of silence so essential for true prayer. Such moments of liturgical silence prepare us “to listen to every word with discerning, and catch hold of its meaning.”

Prayer is an offering, and it must never be forgotten that it is offered in the presence of God, who sees through all pretensions. Aphrahat takes us all the way back to the prayer of Abel the Just, whose offering was acceptable to God because of his purity of heart. Turning to Christ, Aphrahat stresses the communal or social aspects of prayer as epitomized in Matthew 5: 23-24, where Jesus admonishes that you must first be reconciled with your brothers and sisters before approaching the altar of God. This reconciliation has two aspects. First of all, it involves seeking forgiveness for one’s own transgressions. What is perhaps more difficult is the forgiveness of others, but as Aphrahat teaches, if you do not forgive, your offering is in vain.

Aphrahat insists upon a crucial connection between true prayer and love of neighbor . The requirements of liturgical prayer, important as they are, must never be used as an excuse to avoid helping anyone truly in need of it, for authentic prayer in the end consists in a pure love of God that manifests itself in an unfeigned service to our fellow human beings:

“Thus you must forgive your debtor before your prayer; only after that, pray: when you pray, your prayer will thus go up before God on high, and it is not left on earth…Give rest to the weary, visit the sick, make provision for the poor: this is indeed prayer…Prayer is beautiful, and its works are fair; prayer is heard when forgiveness is to be found in it, prayer is beloved when it is pure of every guile, prayer is powerful when the power of God is made effective in it. I have written to you, my beloved, to the effect that a person should do the will of God, and that constitutes prayer.”

*All quotations taken from Aphrahat ˜Demonstration on Prayerˇ Found in ˜The Syriac Fathers on Prayer and the Spiritual Life. Edited and Translated by Sebastian Brock. Cistercian Publications. 1987.

Here is a piece I just published on the blog of Systematic and Historical Theology at the University of St Andrews, where I teach. It is a reflection on what St Bonaventure has to say about the Prophetess Anna in Luke’s Gospel:

Lately I have been thinking of plans for the next Leeds Medieval Congress, which in turn reminded me of one of my favourite altars in England, the Blessed Sacrament chapel with the Pugin Reredos in Leeds Roman Catholic Cathedral. I am already looking forward to some quiet contemplation there in that lovely urban oasis.

This Victorian work of beauty made me also think of one of my oldest heroes, Cardinal (now Blessed) John Henry Newman, and a lovely prayer of his which unites Marian devotion to the longing for greater and eternal union with the Sacred Heart of Jesus. I share it in the hope that it may find resonance with some of you as it does for me, to help nourish hope, strength, and expectation this season of Advent.

O Mother of Jesus, and my Mother,

let me dwell with you, cling to you

and love you with ever-increasing love.

I promise the honour, love and trust of a child.

Give me a mother’s protection,

for I need your watchful care.

You know better than any other

the thoughts and desires of the Sacred Heart.

Keep constantly before my mind the same thoughts,

the same desires, that my heart may be filled

with zeal for the interests of the

Sacred Heart of your Divine Son.

Instill in me a love of all that is noble,

that I may no longer be easily turned to selfishness.

Help me, dearest Mother, to acquire

the virtues that God wants of me:

to forget myself always,

to work solely for him,

without fear of sacrifice.

I shall always rely on your help

to be what Jesus wants me to be.

I am his; I am yours, my good Mother!

Give me each day

your holy and maternal blessing

until my last evening on earth,

when your Immaculate Heart will present me

to the heart of Jesus in heaven,

there to love and bless you and

your divine Son for all eternity.

Amen

Sermon given at All Saints in St Andrews

October 21, 2018 (22nd Sunday after Pentecost)

“But it is not so among you; but whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all.”

There are strong and clear messages for us in today’s readings, both about who Jesus is, and how he accomplished his Mission, and no less significant, how we who want to be his followers must strive to exercise our own discipleship. Clearly Christ came to save us and redeem us by becoming for us the Suffering Servant so powerfully described by Isaiah in today’s first reading. His suffering and humility were quite real, and his redemptive work no easy path. As Christ’s mission progressed, and as he approached Jerusalem and his redemptive Passion, Jesus often would give hints to his Apostles about the nature of his Kingdom, and what it would cost to establish it, a cost described so powerfully in our readings from Isaiah and Hebrews today.

Then we come to our two hapless brothers, James and John, (Peter is not the only Apostle who does not always get it!) who in this remarkable passage make two great mistakes in their approach to Jesus. In the first place, they actually have the temerity, and in Matthew’s version of the story egged on by their mother, a detail which we shall put aside, to tell Jesus that he should give them whatever they ask for. Jesus could have given them right then and there a rebuke, but he chooses to let them continue and ask, giving them the chance, for example, to echo the humble petitions of the Lord’s Prayer which they had already been taught. Instead they ask for something seemingly even more outrageous, namely a fantasy of honor, to sit on his left and right hands when he comes into his kingdom and power. But whatever the two enthusiastic brothers may have been imagining, Jesus makes it clear how much the apostles did not know what they were saying, and refers to the Cup that He must drink:

As St John Chrysostom comments,

“Jesus says therefore, “Can ye drink it?” as much as to say, You ask me of honours and crowns, but I speak to you of labour and travail, for this is no time for rewards. He draws their attention by the manner of His question, for He says not, Are ye able to shed your blood? but, “Are ye able to drink of the cup?” then He adds, “which I shall drink of.”

Clearly the intense service would be that of the suffering Servant, and as St Jerome says,

“By the cup in the divine Scriptures we understand suffering, as in the Psalm, “I will take the cup of salvation;” and straightway He proceeds to shew what is the cup, “Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints.”

(The Sons of Zebedee approaching Christ, Friedrich Heinrich Füger)

As if this were not enough, then the rest of the Apostles also fall into the pits of pride, muttering angrily about the affront given by James and John to their own imagined merited places of honour.

This whole episode makes the apostles incredibly worked up and agitated. In another famous passage when the apostles were becoming overly impressed with themselves, Christ brought forward a child in their midst, and admonished them that they needed to become childlike. Here he uses another approach, to calm their disquiet, and instead of responding in angry chastisement, the Lord uses the opportunity to teach them something fundamental. As John Chrysostom puts it,

“ By thus calling them to Him, and speaking to them face to face, Christ sooths them in their discomposure; for the two had been speaking with the Lord apart by themselves. But not now as before does He do it by bringing forward a child, but He proves it to them by reasoning from contraries; “Ye know that the princes of the Gentiles exercise dominion over them.””

Before we are too hard on the apostles, who unlike us had not yet had the benefit of witnessing the Resurrection and strengthened by Pentecost, we should recall that this particular temptation, to embrace the way of the princes of the Gentiles, is not something that faded away in time. Far from it, it is sadly often found in church history, particularly among those who convince themselves that they are doing something good. For me, this passage called to mind something the Venerable Bede relates about those who were the founders of the church in Britain, thus the founders of our own Christian traditions.

The pagan Anglo-Saxons had conquered and driven the Celtic British Christians into the Western regions, what we now call Wales and Cornwall, and there was no love lost between these British Christians and their enemies and conquerors. When the future St Augustine of Canterbury arrived as a missionary from Italy sent by Pope Gregory, bringing with him the customs and traditions of Rome which by now differed from the older British ones, from his Roman point of view he expected the Celtic Christians to accept his authority. A meeting was arranged by the two sides, and Bede tells us what happened:

Seven bishops of the Britons, and many most learned men, were to go to the aforesaid council, but first they consulted a certain holy and discreet man, who lived as a hermit among them, and asked him, whether they ought, at the preaching of Augustine, to forsake their traditions. He answered, “If he is a man of God, follow him.” – “How shall we know that?” said they. He replied, “Our Lord says, Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me, for I am meek and lowly in heart.” If therefore, Augustine is meek and lowly of heart, it is to be believed that he has taken upon him the yoke of Christ; and offers the same to you to take upon you. But if he is stern and haughty, it appears that he is not of God, nor are we to regard his words.” They insisted again, “And how shall we discern even this?” – “Do you contrive,” said the hermit, “that he may first arrive with his company at the place where the synod is to be held; and if at your approach he shall rise up to you, hear him submissively, being assured that he is the servant of Christ; but if he shall despise you, and not rise up to you, whereas you are more in number, let him also be despised by you.”

Now of course Augustine, following the normal Roman way for a bishop, sat in a chair waiting for them, and, following the old Roman ways, drawn from imperial protocol, did not stand, and it probably never entered his mind to stand. So it happened that when the British bishops came, Augustine was sitting on a chair, and when they observed this, like the apostles in our reading today, Bede tells us, fell into a passion, and charging him with pride, endeavoured to contradict all he said. He said to them, “You act in many particulars contrary to our custom, or rather the custom of the universal church, and yet, if you will comply with me in these three points, viz. to keep Easter at the due time; to administer baptism, by which we are again born to God, according to the custom of the holy Roman Apostolic Church; and jointly with us to preach the word of God to the English nation, we will readily tolerate all the other things you do, though contrary to our customs.” They answered they would do none of those things, nor receive him as their archbishop; for they alleged among themselves, that “if he would not now rise up and stand for us, how much more will he contemn us, as of no worth, if we shall begin to be under his subjection?” To whom the man of God, Augustine, is said, in a threatening manner, to have foretold, that in case they would not, all would go poorly for them.”

Here both sides failed to understand one another, standing upon their rights and what was due to them as both of their cultures, whether the Celtic or the Roman, understood it. Standing on ceremony, threatening and despising one another, embracing all too much the way of the princes of the gentiles as they understood them, perhaps almost hoping that the other side would make a mistake they could pounce upon, the meeting failed and cemented a legacy of distrust for generations.

But Bede has more to say, namely the witness of the saintly bishop Chad. He had been made a bishop for York and the North by the saintly Aidan of Lindisfarne in the Celtic manner, and was known for his itinerant preaching on foot in the countryside, care for the poor, his own poverty and simplicity and dedication to reading and praying with Scripture, a care for the sick which eventually led to his own death from plague. Due to confusion a dispute arose and when the new archbishop, St. Theodore of Canterbury, arrived in England, he charged Chad with improper ordination. In humility Chad resigned, but when he actually met Theodore, the archbishop was so moved and impressed with Chad’s transparent humility, his sincere self-effacement, that Theodore himself physically helped the reluctant Chad to mount a horse, and when another bishop died he asked the king to appoint Chad as the bishop’s successor. Peace had come to the Church in the North.

Jesus knows how hard this is, how strong the temptation is to insist on the prerogatives of the princes of the Gentiles, even for saints like Augustine or Theodore of Canterbury; and that is why, as Jerome says, Jesus did not chastise the apostles, but rather

“the meek and lowly Master neither charges the two with ambition, nor rebukes the ten for their spleen and jealousy; but instead the Gospel says, “Jesus called them unto him.”

Jesus knows us very well; he knows we have this temptation, this weakness, to want recognition, to get our due, to be revered, to seek power even when it is in the cause of seemingly good things. He knows from his own experience it is not always the case to encounter a posture of receptivity, and instead to be met with constant judgement, misunderstanding, and sometimes rejection and much worse. Perhaps He was patient and gentle with the apostles because He knew that they themselves would someday imitate Him as Suffering Servant even to the point of their own martyrdoms, as Tradition tells us.

We may not, hopefully, be called to literally imitate every aspect of the Suffering Servant, but we are nonetheless called to our own form of participation in the servant hood of Christ. This was the message Jesus gave us in today’s Gospel and other similar passages, and most dramatically and poignantly right before his Passion, when he washed the feet of the disciples, and directed them to a life of service, that is ministry. It may well indeed lead to martyrdom, but more likely for most of us a life of daily service, marked by a sincere attentiveness to the needs of the day, attentiveness to the needs of those around us, a posture of receptivity as we become as individuals and a church and society what one spiritual teacher once called “people of the towel and water.” As Evelyn Underhill once beautifully put it:

“To the eye of faith the common life of humanity, not only abnormal or unusual experience, is the material of God’s redeeming action. As ordinary food and water are the stuff of the Christian sacraments, so it is in the ordinary pain and joy, tension and self-oblivion, sin and heroism of normal experience that His moulding and transfiguring work is known…A deep reverence for our common existence with its struggles and faultiness, yet its solemn implications, comes over us when we realize all this; gratitude for the ceaseless tensions and opportunities through which God comes to us and we can draw a little nearer to Him—a divine economy in which the simplest and weakest are given their part and lot in the holy redemptive sacrifice of humanity and incorporated in the Mystical Body.”

Let us ask Jesus for the insight to see these opportunities all around us. Let us conform our will to his, so that when we pray that he does what we want, we are actually asking him for the right thing, that His actual will be done, that we be strengthened to be servants in the greatest task of all, humbly going about doing the small but crucial tasks that make his Kingdom come. That way, the people we encounter will recognize the face of Christ in us, just as we recognize him in them. When we practice this servant way of love, no matter what befalls us, we know that Christ will be near us, and welcome us, recognizing us as his brothers and sisters, ready to share every aspect of his life, to drink with him not just the cup of suffering, but indeed the cup of eternal salvation. And then, we will rejoice to hear spoken both to ourselves and all those around us the lovely words of the Prophet Isaiah,

“Those who love me, I will deliver;

I will protect those who know my name.

When they call to me, I will answer them;

I will be with them in trouble,

I will rescue them and honour them.

With long life I will satisfy them,

and show them my salvation. Amen.”

Sermon given at All Saints, St Andrews July 29, 2018 (Feast of St Olaf, and Sea Sunday)

[Readings: 2 Kg 4.42-44; Ps 145.10-19; Ephesians 3.14-21; John 6: 1-12]

“All thy works shall give thanks to thee, O LORD, and all thy saints shall bless thee! They shall speak of the glory of thy kingdom, and tell of thy power, to make known to the sons of men thy mighty deeds, and the glorious splendor of thy kingdom.”

There can be no doubt the Scriptures are often full of praise for the glories of nature, and how our observance and appreciation of nature calls to mind God’s divine power as Creator, Sustainer and the Lord of Creation. At extraordinary times this power over creation is often worked through human agents, such as the Prophet Elijah in our first reading, and of course miracles, or extraordinary signs of God’s power, are events most dramatically also associated with the life and ministry of Jesus himself, from the Virgin Birth through the Wedding at Cana to the multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes, walking on water, to the raising of Lazarus and His own glorious Resurrection. The fact that the prophets could work miraculous signs, and the signs worked by Christ, is integral to the Biblical Narrative, as we saw in our first reading. Interestingly, control over nature has often been expected in the lives of the saints in the Christian folk tradition. Today as it happens, is the Feast of St Olaf, the patron of Norway, an eleventh century royal seafarer who ranged far and wide in the northern world fighting battles as far afield as London and Russia.

Eventually as king of Norway who set out, often by rather stern methods, to unite the country and Christianise its hinterland, Olaf was killed in battle by his pagan enemies on this day in 1030. He was soon venerated as a saint, ultimately as Norway’s Eternal and Apostolic King, Olaf’s memory is celebrated in Catholic, Orthodox, and various Anglican and Lutheran calendars, a recognition that his shrine in Trondheim became a great centre of pilgrimage in Scandinavia, not unlike St Andrews here, until the Reformation. And not unlike St Andrews, pilgrimage is now being revived in Norway much like in Fife, pointing to a strong spiritual need that pilgrimage has an enduring power to satisfy.

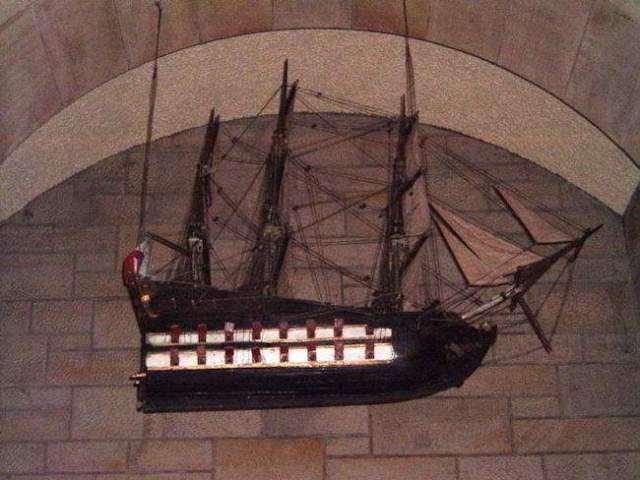

Trondheim cathedral

According to one story popular in the middle ages, Olaf posthumously had defeated a sea monster who was threatening some sailors, and one could still point to the spot where he had dashed it against a cliff! Here we have a bit of Thor defeating the Midgard serpent, but also, significantly, Christ walking on water and calming the storm. It gave comfort to sailors in their dangerous work to know that God and his saints could work such miracles of power. In this beautiful church, on a day when in our collection we call to mind fishermen and sailors, and gaze at the lovely votive ship we have hanging in the nave of the church, and as someone who has a long line of Norwegian sailors and fishermen in my own ancestry, I must admit to being moved by the faith and piety that these tales nourished. And even if God did not always choose to vanquish enemies on the field of battle, as Olaf experienced in his last battle, His Power meant much more than that, and trust in Him led to eternal life.

Votive Ship in the nave of All Saints

Jesus certainly could do signs, perform miracles of power and in fact the Gospel of John is famously structured around these signs; and there is no doubt Jesus is portrayed by John as fulfilling the promise of OT prophets, and the lectionary today makes that connection clear. But this connection between the Old Testament and the miracles of Jesus goes back to early Church interpretation, as St John Chrysostom pointed it out in the 4th century when preaching on these texts. Chrysostom felt that in this passage we just read, the Apostle Andrew (and we can take heart here as he is our patron), is very conscious of his Bible, as, following the remark of Philip, he probes Jesus further on the need to feed the crowd, saying: “There is a lad here who has five barley loaves and two fish; but what are they among so many?” Chrysostom goes on to say:

“I believe that Andrew did not speak without a reason, but because he knew of the miracle Elijah had wrought with the barley loaves. For the prophet had fed 100 men with twenty loaves. Andrew’s mind therefore rose somewhat higher; but he did not rise to the heights, as appears from what follows: But what are they among so many? For Andrew reckoned that He who was wont to perform miracles would make fewer from the few, and more from the greater number. But this was not so. For He could as easily feed the multitudes from a few loaves as from many. For he needed no subject matter. But lest created things seem outside the power of His wisdom, He uses created things to work His wonders.”

John’s gospel presents Andrew as a significant figure among the disciples of Jesus. Andrew is not only the ‘first called’ among the apostles, and the one who introduces his brother Simon Peter to Jesus, but also most importantly he had been a disciple of John the Baptist. Presumably Andrew witnessed John the Baptist being questioned, and responding in the negative, about whether he was the Messiah or Elijah, and must have pondered all this as he began to follow Jesus. In this context of the hungry multitude, Andrew may well have had the Elijah story of feeding the 100 in mind as he continued to discern who Jesus was, and this would go along the lines of what Chrysostom speculates. Andrew must have been aware that John the Baptist did not perform miracles, as Elijah did and the Messiah was expected to do, and in a sense his whole life was a sign (medieval exegetes loved to discuss this!). The narrative of John seems to hint that Andrew, the former disciple of the Baptist, feels Jesus can and perhaps should do something here, and his words are perhaps a gentle hint of things he thinks Jesus is capable of, and like Mary at Cana, is prompted by divine inspiration to move beyond the words of Philip, to prod Jesus to set the stage for a further sign. And so Jesus complies and exceeds even the miracle of Elijah.

But there is more. This miracle should indeed induce us to give thanks and great glory to God for his works, both his creation and his lordship over creation; As the fourth century writer St Hilary put it in response to this miracle:

“Five loaves are accordingly placed before the multitude, and broken in pieces. The new increase flowing imperceptibly from the hands breaking the fragments; the bread from which they are broken not growing less, while the portions broken off continue to fill the hand that is breaking them. Neither sense nor sight can follow the progress of the wondrous operation; That is now which was not; that is seen which is not comprehended; what alone remains is to believe that God can do all things.”

Yet as we accept these signs for what they are, and the happiness and joy and wonder their contemplation rightly brings us, we can grow uneasy as we realize that this is not enough, that Jesus is calling us to do something more than follow Him because of His signs. His plan is clearly not just to keep multiplying bread and calming storms and walking on water, no more than it is to keep healing every single person suffering from an illness. It is clear, often to our dismay, that we cannot expect this sort of sign at all times, in every circumstance.

Jesus in fact in the Gospel at several places expresses frustration that the crowds only want signs, whereas he wants them to focus on something else, namely the message and teaching that accompanies these signs. Jesus, as Andrew found out, cannot only do many times over what Elijah did, but that, just as there was someone greater than Solomon here, there was also someone greater than Elijah here. Following this miracle Andrew and the others were soon to hear Jesus teach something about himself which was much harder to understand but exponentially greater. For the rest of Chapter 6 in John’s gospel Jesus will move beyond this sign and miracle of the loaves to claim and assert in breath-taking and quite shocking terms to his audience that He Himself is the Bread of Life, which we are first of all called upon to hear and ponder and allow to work into the very marrow of our souls; likewise there is now seen from the vantage point of this side of the events known as the Last Supper, Passion and Resurrection, a clear Eucharistic meaning to his words and deeds, which bring out for us the fullness of the meaning of the loaves and fishes; and in just a few moments we will approach the altar to receive his very body and blood. Word and Sacrament working together, Jesus the bread of Life will renew us and transform the inner man as described by St Paul.

Over 12 centuries ago, one of the great lights of the early Church in the North, the remarkable teacher and exegete Alcuin of York, made this very connection as he wrote about how Christ performed this sign we ponder today as he approached Jerusalem for the great feast of Passover:

“That Christ fed them at the approach of the Pasch signifies that whosover desires to be nourished by the Bread of the Divine Word, and by the Body and Blood of the Lord, should make a spiritual pasch; that is, pass over from the vices to the virtues.”

Echoing the Psalm we prayed today, Alcuin continues,

“The eyes of the Lord are truly spiritual gifts, which he mercifully bestows upon His elect, whenever He turns His eye upon them: that is, when he bestows on us the rewards of filial devotion.”

Every time we approach the altar, as loving and humble children of God, filled with the grace of what Alcuin calls ‘filial devotion,’ we, in a very real sense are on a pilgrimage, no less than those who went and still go to the shrines of St Olaf or St Andrew. We are on a journey to encounter the living God, and we cannot do it by ourselves. Participation in God’s glory depends on his grace and the gift of faith, but we in all humility must recall we are in the presence of something greater than Solomon and Elijah here, although they and all the company of saints, Olaf and Andrew included, and hosts of angels, are with us right now, offering praise and thanksgiving, that cloud of witnesses whose fellowship should be our joy and delight. As Alcuin and the whole tradition of the Church and the very words of Scripture urge us over and over again, we can confidently hope and ask to move beyond the veils that so often cloud our understanding, vision and way, to move beyond the signs to the reality behind them, that is so much more than we can ever imagine, the God Who is Love, so capable of changing us and transforming us into the persons God wants us to be; to bring about the renewal of our inner selves, as St Paul says,

“…that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith; that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have power to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ which surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fulness of God.”

This is our destiny as Christians, this is what we want, this is why we are here today; as we have pondered God’s Word in Scripture, and find Him also in those all around us in this congregation, and encounter Him in the Eucharist, let us ask the Lord for this right now, in the words of Alcuin:

Eternal light, shine into our hearts,

Eternal Goodness, deliver us from evil,

Eternal Power, be our support,

Eternal Wisdom, scatter the darkness of our ignorance,

Eternal Pity, have mercy upon us;

that with all our heart and mind and soul and strength

we may seek your face

and be brought by your infinite mercy to your holy presence;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

My Sermon, Opening Service St Mary’s College, St Andrews September 2017

It is a pleasure to be here with you at this opening of a new academic year, in this ancient and sacred place, a time of new beginnings and opportunities. Welcome to all of you who are new here, to St Mary’s and the university, embarking on an exciting adventure. It is also a time for those of us returning to renew old friendships and for many, the first day of what will become very important friendships and relationships of all kinds. Also, I would say, it is a time to set out for ourselves our goals and aspirations for our personal lives, and I hope and urge you today that this should involve ways of thinking about what we hope to gain from our studies, and how do our studies relate to our lives as a whole, including our spiritual lives, the life of our souls.

Our first reading today gives us an idea, the beginnings of a program of our course of life. It puts before our eyes the great Solomon, who though by no means perfect in his later life choices, and all too human, mistakes and all, is remembered for how he responded to God when asked a very important question. As we just heard, Solomon very famously when offered his choice of gifts from God, asks for the gift of Wisdom, and in so doing sets up a model of what all those in responsibility should ask for and aspire to.

What is Wisdom? This is a big question!

While it often depends on knowledge, it is not merely the same as that. Computers can contain limitless knowledge, but they are not wise. Memorizing math tables, historical dates, or sports statistics, can give us a type of knowledge, but in itself is not wisdom. Experience when added to knowledge can bring a certain sort of wisdom, but only if we actually heed it and learn from it. Learning the Creeds and catechisms, memorizing the names of all the books of the Bible and even being able to quote from them, does not in itself make us wise. Medieval thinkers spent much time explaining the difference between mere knowledge of a type, and true wisdom. We certainly could turn to many of the world’s great religions, to the Greeks and Romans, to Buddhism and Taoism, to Islam and Hinduism, to tales of Odin in Norse mythology and the sages of Native Americans, for good definitions of Wisdom, and how to make our way in the world and avoid foolishness.

But what about our friend Solomon? According to King Solomon, as tradition records it in the biblical Wisdom literature, basically wisdom is gained from God, “For the Lord gives wisdom; from His mouth come knowledge and understanding” Proverbs 2:6. And through God’s wise aide, one can have a better life, marked by good conduct: “He holds success in store for the upright, he is a shield to those whose walk is blameless, for he guards the course of the just and protects the way of his faithful ones” Proverbs 2:7-8. “Trust in the LORD with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding; in all your ways submit to him, and he will make your paths straight” Proverbs 3:5-6.

There are various verses in Proverbs that contain parallels of what God loves, which is wise, and what God does not love, which is foolish. For example in the area of good and bad behaviour Proverbs states, “The way of the wicked is an abomination to the Lord, But He loves him who pursues righteousness (Proverbs 15:9). In relation to fairness and business it is stated that, “A false balance is an abomination to the Lord, But a just weight is His delight” (Proverbs 11:1; cf. 20:10,23). On the truth it is said, “Lying lips are an abomination to the Lord, But those who deal faithfully are His delight” (12:22; cf. 6:17,19). These are a few examples of what, according to Solomon, or those who passed down his teachings, are good and wise in the eyes of God, or bad and foolish, and in doing these good and wise things, one becomes closer to God by living in an honorable and kind manner.

And famously in the book of Ecclesiastes, the sage concludes that all life’s pleasures and riches, and even wisdom, mean nothing if there is no relationship with God.

The Epistle of James is often said to be the New Testament version of the book of Proverbs. It reiterates Proverbs message of wisdom coming from God by stating, “If any of you lacks wisdom, you should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to you.” James 1:5. James also explains how wisdom helps one acquire other forms of virtue, “But the wisdom that comes from heaven is first of all pure; then peace-loving, considerate, submissive, full of mercy and good fruit, impartial and sincere.” James 3:17. In addition, James focuses on using this God-given wisdom to perform acts of service to the less fortunate. So the fruits of wisdom are very desirable, and should show themselves in our own behavior, including how we treat others.

Fair enough, but where does this relationship with God come from? How do we find it in our lives?

If we seek to be truly wise, while doing so, never cease to pray for it.; take your studies seriously; find good mentors, among the staff and your friends, among pastors, and among great and perennial books. There are so many voices now, especially with the internet. It becomes crucially important to pray for discernment to evaluate what you are hearing and learning, and how to apply it to questions that matter for you and the churches and the world.

I have found much wisdom in the life and teaching of a great monk Benedict of Nursia, the author of a rule for monastic life that would have a profound effect on the church and all of western culture. He knew a few things about cultivating wisdom. He knew that it came with a balance of prayer with others, or liturgy; prayerful reading of the Scriptures, meditating on them and making them our own; and useful work and wholesome recreations. There is much wisdom in such a balance for all of us, whether students or staff, and I will come back to this in a few minutes.

St Benedict in his famous rule exhorts us to listen to the words of the master, and we should do that. But we also must be open to wisdom when it comes from unexpected places, as this same Benedict cautions us that we must listen even to the voices of those who are junior in the monastery. Our staff must be open to the voices of their students, and perhaps, dare I say it, even be prepared to find wisdom there!

Most importantly, Benedict ultimately exhorts us that we must seek wisdom in Scripture, as he puts it: what word of the NT and OT is not full of guidance for life. To turn knowledge of Scripture into wisdom, we must first have the knowledge. But that is not enough! For then it must be joined with humility, and most all charity. A wise teacher I admire greatly was Walter Hilton, a great English spiritual teacher of the 14th century; he was an Augustinian canon, who lived a form of religious life very similar to the canons who lived and worked and prayed in St Andrews cathedral a few hundred feet from us right now. Walter Hilton was known as a great spiritual advisor, and, following the teachings of St Paul, he had this to say about the way knowledge of Scripture becomes wisdom when approached in the right Spirit, in prayerful attentiveness to the grace of God :

“Learned men and great scholars have devoted great effort and prolonged study to the Holy Scriptures… employing the gifts which God gives to every person who has the use of reason. This knowledge is good … but it does not bring with it any spiritual experience of God, for these graces are granted only to those who have a great love for Him. This fountain of love issues from our Lord alone, and no stranger may approach it. But knowledge of this kind is common to good and bad alike, since it can be acquired without love, … and men of a worldly life are sometimes more knowledgeable than many true Christians although they do not possess this love. St. Paul describes this kind of knowledge: “If I had full knowledge of all things and knew all secrets, but had no love, I should be nothing.” … Some people who possess this knowledge become proud and misuse it in order to increase their personal reputation, worldly rank, honours and riches, when they should use it humbly to the praise of God and for the benefit of their fellow Christians in true charity… St. Paul says of this kind of knowledge: “Knowledge by itself stirs the heart with pride, but united to love it turns to edification.” By itself this knowledge is like water, tasteless and cold. But if those who have it will offer it humbly to our Lord and ask for His grace, He will turn the water into wine with His blessing.”

Walter Hilton

For the Christian ultimately, knowledge joined to humility and charity becomes wisdom when it is sought from Christ, centered in Christ, and lived in obedience to how Christ wants us to live, overflowing and transforming our relationships with those around us, our neighbors.. Over 300 years ago, a New England poet and pastor, Reverend Edward Taylor, served for decades in what was then the wilderness of the Connecticut River Valley in Westfield, Mass. He wrote many poems on the Eucharist and saving power of Christ, drawing deeply not only on his own Reformed and Calvinist context, but on themes that had deep roots back through the middle ages and into the Church Fathers.. In one sermon given to his frontier congregation he spoke of wisdom this way, using homely images but also the image of the fountain which we just saw in Walter Hilton:

“There is a natural desire of Wisdom as an Essential Property of the Rational Nature…And in great desires of these Treasures of Wisdom betake yourselves to Christ to partake of them. Where should the hungry man go for good but to the Cooks shop? Where should the thirsty go for water except to the Fountain? No man will let his bucket down into an empty well if he be aware of it. No man will seek riches in a beggars cottage. He that would be wealthy must trade in matters profitable. So if thou wouldst have spiritual treasures, trade with Christ. Wouldst thou have Heavenly Wisdom? Go to Christ for it.”

Let us then go to Christ, who is Love and who indeed is Wisdom incarnate. And what today did Wisdom tell us, in the Gospel, as the Eastern Orthodox liturgy proclaims, before the Gospel is read, “Wisdom! attend!!”

Our gospel reading today, the words of Wisdom incarnate, delivers to us the warning against rash judgment of others, reminds us of the need to practice self awareness of our own faults, and to concentrate on those, rather than spending our time and energy complaining about what is wrong with everyone around us.

Instead, we are invited and indeed exhorted to assume a posture of graciousness, and hospitality; This does not mean a suspension of common sense and a listless, passive acceptance of evil. But what it does call for is a realization of the need to treat others with compassion and understanding, much as we would like others to treat us. This is Wisdom speaking, this is the Golden Rule, the foundation upon which we must build our lives in community,. This is wisdom, the summation of the Law and the Prophets; This, taken even further and joined with charity and forgiveness, is what Jesus commands us to do, instructs us on how to behave if we expect our own prayers to be heard, if we expect our own faults to be forgiven, and to make any advance in the spiritual life. To be wise we must indeed begin with the starting point of the Golden Rule, enlarged and transformed and deepened by the power of the Holy Spirit.

This can be hard, especially with all of the stresses of life. It is hard to keep ourselves centered in Christ, to keep our spiritual equilibrium. We must take steps, at all times asking God’s help and grace, to have a life organized in such a way that allows us to make room to cultivate authentic wisdom, to allow us to see God in ourselves, in our neighbor, and in our work and studies. Let me end today by giving a few suggestions on how to do this, which are not original to me, but instead take us deeply into the tradition for guidance, back to Benedict whom I mentioned before.

For Benedict, a life centered on God, involved being attentive to our own spiritual needs and the needs of those around us. He truly felt that at the heart of spiritual life and wisdom was the profound idea that we need to respect and listen to others in our spiritual lives, particularly those with more experience. We have to sincerely believe that what other people have to say can really help us. As the gospel tells us today, we do not sit in constant judgment on others, eager and willing to pounce on their words and criticize them; but rather we should listen to them with an attentive regard, allowing the Holy Spirit to work on us through their words, and become a part of our own process of spiritual growth and discernment, in other words to help us grow in true wisdom.

Benedict suggested a way of dividing the day up that allows us to have spiritual balance, to keep us from getting burned out and also to keep us from neglecting what is important. First of all we must make time in our week to pray with others, for the liturgy and common prayer. This includes making sure that every day, not just on Sunday, we make at least some time, preferably the morning and evening, to offer up our prayers to God, in communion with those doing so throughout the world. Secondly, we must make at least a small amount of time for Spiritual reading, a prayerful reading of Scripture or some other worthy text. This ensures we are not just staring at ourselves, but rather attentively listening to God speak to us through his Word. This will renew and nourish us. As one church father put it, “If a person wants to be in God’s company, he must pray regularly and read regularly. When we pray we talk to God; when we read. God talks to us. All spiritual growth comes from reading and reflection; By reading we learn what we did not know; by reflection we retain what we have learned.”

And finally, and not least, there is our work. We all have jobs and responsibilities, including the work of being a student and teaching and research and administration. We all must do our work, and the important thing is that this work be done in a sprit of offering it as a gift to God. Benedict says we must begin all our work with a prayer, not a bad practice for us to emulate. Whatever our work is, if done in the proper spirit, like reading and praying and liturgy, it becomes a type of prayer. In this way our work, our tasks for the day are not something that are keeping us from doing something else, but are themselves the stuff of holiness, opportunities to grow in love of God and neighbor, to be holy, to be truly wise. And to be better at this, we must be sure to balance our work with healthy recreations.

So ask for God’s help in the coming year to balance all of these needs, to find meaning in our work, studies, and relationships, to find God and Christ in all we do and aspire to, and in this way to pursue the wisdom that really matters. And as we strive to do this together, we can join each day in the prayer of St Benedict, “let us prefer nothing whatsoever to Christ, and may he lead us to everlasting life.” Amen.